——一份关于权利分层与社会内卷的观察报告

文/HuSir

在大洋国的宪章中,人权是一个被反复强调的词。法律文本庄严而宏大,几乎涵盖了现代文明所认同的一切基本权利:言论、集会、游行、出版、信仰、人身自由、迁徙自由、财产权、人格尊严……字句清晰,语气坚定,仿佛每一个公民都站在权利的中心。

但如果一个外来的观察者愿意在大洋国生活几年,慢慢接触普通人的日常,他很快会发现一个令人困惑的事实:这些权利似乎存在,却并不真正属于所有人。

在纸面上,权利是平等的;在现实中,权利是分层的。

权利不平等的背后,是更严重的利益不平等;权利分层,正是整个社会内卷的制度根源。

在大洋国,权利分层并非写入任何法律文本,却深植于日常生活的每个细节。普通公民在表达公共意见时需自我审查、回避禁区,而权力体系内部则拥有更安全的讨论空间;普通人组织集会需层层审批,稍有越界即被认定为非法,权力系统内部的各种动员与联络却天然合法;普通人的出行、迁徙、司法维权、医疗资源获取与隐私保障充满不确定性,而处在权力网络中的群体则享有更稳定、更优先、更受保护的通道;普通家庭在教育与医疗上承受激烈竞争与高风险,而权力体系内部家庭则通过制度化渠道获得更可靠的保障。这些差异并不通过法律明示,却通过制度运作与长期习惯形成稳定结构,使人们逐渐明白:权利的真实重量,不取决于宪章的文字,而取决于你与权力中心的距离。

老大哥所追求的权利集中,即极权统治,背后是利益的极端集中;人民权利的不断收缩,正是这种权力一点点侵蚀的直接后果。在大洋国,因此,所谓的计划经济和中央调控,不过是其权利不平等分配的粉饰说辞。资源配置、机会获取与风险承担并未在社会成员之间均匀分布,而是沿着权力结构层层倾斜。权利的分层,使得不同群体在教育、医疗、司法、就业与资本获取等关键领域的起点与成本出现系统性差异。当上升通道被权利结构提前划定,竞争便不再是能力与努力的较量,而是位置与关系的博弈。普通人为了争夺有限的生存空间被迫投入更高强度的时间、情绪与资源,社会整体因此陷入高消耗、低效率、低安全感的内卷循环。表面上是个人竞争,实质上却是制度不平等长期积累后的集体困局。

然而,大洋国并没有公开宣布人权等级制度,但所有人都能从上述一系列“不方便”隐约感觉到它的存在。不像印度的婆罗门教,等级鲜明,不容质疑。大洋国的一个普通公民若在公共场合谈论政治、表达不满、组织活动,往往需要反复衡量后果;而处在权力结构内部的人,却拥有更宽广、更安全的表达空间。法律对两者使用同样的条文,却在执行中呈现出完全不同的结果。这种差别并非来源于个人品德,而是来自一种稳定运转的社会结构:权利与权力的距离,决定了权利的真实重量。

在大洋国,法律更像是一种单向约束工具。它被用来规范普通人的行为,却很少成为约束权力本身的枷锁。宪章所承诺的自由与尊严,在普通人的日常生活中,常常退化为一种需要“审批”和“配合”的资格。

于是,“权利”这个词悄然发生了变化:它不再是个人对权力的边界保护,而逐渐变成了个人是否符合某种政治与思想期待的证明。最讽刺的是,这一切并不需要公开宣布。它通过制度、语言、文化与长期的心理适应自然完成。

在这种环境中,大洋国的普通人逐渐学会了一种新的生存智慧:沉默比表达安全,服从比质疑省心,适应比坚持现实。人们仍然会在文件与口号中看到“人人平等”,却在日复一日的生活里感受到一种无形的等级秩序。这不是法律条文的问题,而是权力结构的问题。

真正的问题因此浮现出来:如果权利只在不触碰权力边界时才成立,那么它还是权利吗?如果自由需要持续证明忠诚才能存在,那么它还是自由吗?也许,大洋国最深的困境并不在于制度本身,而在于人们已经逐渐习惯了这种差异,并将其视为“正常”。

而当不平等被视为常态,人权便只剩下装饰性的意义。一个社会是否文明,并不取决于它的口号多么响亮,而取决于最普通的人,是否可以在不恐惧的前提下,安心地说话、生活、思考、选择和拒绝。

这,才是人权是否真正平等的试金石。

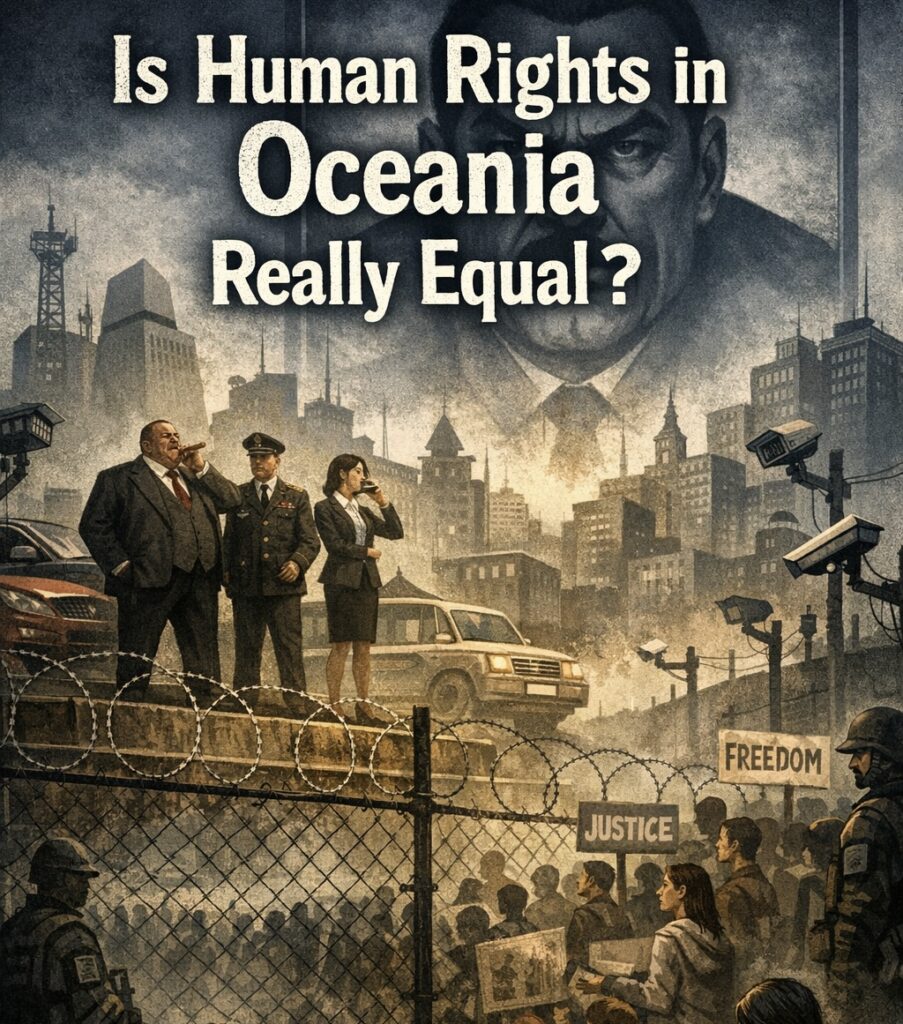

Is Human Rights in Oceania Really Equal?

— An Observational Report on Rights Stratification and Social Involution

By HuSir

In Oceania’s charter, human rights are a repeatedly emphasized concept. The legal texts are solemn and grand, covering almost all fundamental rights recognized by modern civilization: freedom of speech, assembly, demonstration, publication, belief, personal liberty, freedom of movement, property rights, and human dignity. The language is clear and firm, as if every citizen truly stands at the center of these rights.

However, if an outside observer were to live in Oceania for several years and gradually come into contact with the daily lives of ordinary people, they would soon discover a puzzling fact: these rights seem to exist, yet they do not truly belong to everyone.

On paper, rights are equal; in reality, rights are stratified.

Behind the inequality of rights lies an even more severe inequality of interests. The stratification of rights is precisely the institutional root of the society’s deep involution.

In Oceania, this stratification of rights is not written into any legal text, yet it is embedded in the smallest details of daily life. Ordinary citizens must practice self-censorship and avoid sensitive boundaries when expressing public opinions, while those inside the power structure enjoy a far safer space for discussion. Ordinary people must undergo layers of approval to organize gatherings, and even minor deviations can be deemed illegal, whereas mobilizations and coordination within the power system are naturally legitimate. For ordinary people, travel, migration, judicial protection, access to medical resources, and privacy protections are full of uncertainty, while groups connected to power networks enjoy more stable, prioritized, and protected channels. Ordinary families bear intense competition and high risk in education and healthcare, whereas families within the power system obtain more reliable guarantees through institutional channels. These differences are not explicitly stated in law, yet they form a stable structure through institutional operation and long-standing practice, gradually teaching people that the real weight of rights does not depend on the words in the charter, but on one’s distance from the center of power.

What Big Brother pursues is the concentration of rights—namely, totalitarian rule—behind which stands the extreme concentration of interests. The continuous shrinking of the people’s rights is the direct result of this gradual erosion of power. In Oceania, therefore, the so-called planned economy and central regulation are merely rhetorical embellishments for unequal distribution of rights. The allocation of resources, access to opportunities, and distribution of risks are not evenly shared among members of society but instead tilt layer by layer along the structure of power. The stratification of rights creates systematic differences in starting points and costs across key domains such as education, healthcare, justice, employment, and access to capital. When upward mobility is pre-determined by the structure of rights, competition is no longer a contest of ability and effort, but a game of position and connections. In order to compete for limited survival space, ordinary people are forced to invest ever-increasing amounts of time, emotion, and resources, driving society as a whole into a vicious cycle of high consumption, low efficiency, and low security. On the surface, this appears as personal competition; in essence, it is a collective dilemma formed by long-term institutional inequality.

Yet Oceania has never publicly declared a hierarchy of human rights, although everyone can vaguely sense its existence from the many “inconveniences” described above. Unlike India’s Brahmanical system, where hierarchy is explicit and unquestioned, in Oceania an ordinary citizen who discusses politics, expresses dissatisfaction, or organizes activities in public must constantly weigh the consequences, while those within the power structure enjoy a much broader and safer space of expression. The same legal clauses are applied to both, yet their enforcement produces completely different outcomes. This difference does not stem from individual character, but from a stable social structure: the distance between rights and power determines the real weight of rights.

In Oceania, the law functions more like a one-way instrument of constraint. It is used to regulate the behavior of ordinary people, but rarely becomes a shackle on power itself. The freedom and dignity promised by the charter, in the daily lives of ordinary citizens, often degrade into a kind of qualification that requires “approval” and “cooperation.”

Thus, the word “rights” quietly changes its meaning: it is no longer a boundary protecting individuals from power, but gradually becomes proof of whether one conforms to certain political and ideological expectations. Most ironically, none of this needs to be publicly declared. It is accomplished naturally through institutions, language, culture, and long-term psychological adaptation.

In such an environment, ordinary people in Oceania gradually acquire a new survival wisdom: silence is safer than expression; obedience is more convenient than questioning; adaptation is more realistic than persistence. People continue to see “equality for all” in documents and slogans, yet in their daily lives they experience an invisible hierarchy. This is not a problem of legal wording, but of power structure.

The real questions thus emerge: if rights only exist as long as they do not touch the boundaries of power, are they still rights? If freedom can exist only through continuous demonstrations of loyalty, is it still freedom? Perhaps the deepest dilemma of Oceania does not lie in its system itself, but in the fact that people have gradually grown accustomed to this disparity and come to regard it as “normal.”

And when inequality becomes the norm, human rights are reduced to mere decoration. Whether a society is truly civilized does not depend on how loud its slogans are, but on whether the most ordinary person can, without fear, live, speak, think, choose, and refuse in peace.

This is the true test of whether human rights are genuinely equal.